Excavation exposes Roman imperial outpost at its bitter end

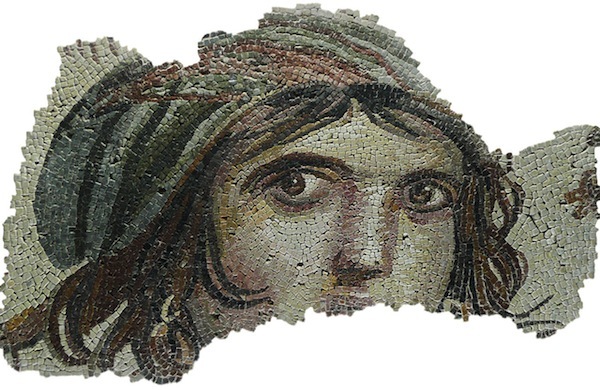

“Gypsy Girl,” one of many mosaics recovered from Zeugma, an outpost city on the fringe of the Roman Empire. Covered by colluvial deposits, the lost city was preserved much as it was the day the city was overrun by the Sasanian Persians, leaving a rich and, for the most part, undisturbed archaeological record.

Photo: Zeugma Mosaic Museum

Like Pompeii, the ancient ruins of Zeugma, a frontier city of the Roman Empire on the banks of the Euphrates River in what is now modern Turkey, stood frozen in time.

Sacked and burned in A.D. 252 or 253, Zeugma was abandoned and became little more than a footnote of troubled times in imperial Roman history. Aside from sporadic looting and the reclamation of building material in antiquity, and covered with colluvial sediments, the site was largely forgotten.

“For the most part, Zeugma was undisturbed,” explains William Aylward, a University of Wisconsin–Madison professor of classics who, under the auspices of the Packard Humanities Institute, recently completed a synthesis of the epic archaeological rescue excavation of the site on the Euphrates before its inundation beneath the waters of a reservoir created by the new Birecik dam. In 2000, a team of as many as 200 archaeologists, in a dramatic race against the rising waters of the Euphrates, conducted a sensational rescue, salvaging stunning mosaics, military equipment, coin hoards and a life-size bronze statue of Mars (hidden in a closet), to put archaeological flesh on the bones of a skimpy historical record of the city’s demise.

William Aylward

“It’s a snapshot of life in the third century on the fringe of the ancient world,” says Aylward, an expert on the cities, sanctuaries and architecture of the ancient Mediterranean. “Zeugma is a site of great archaeological importance because it is in a zone of the ancient world about which we knew very little until this rescue.”

Excavations at Zeugma, the three-volume work edited by Aylward, gathers the descriptions and interpretations of nearly 30 scholars involved in either the rescue work or the decade-long analysis of the objects and buildings unearthed at the city, once a strategically important river crossing and Roman military garrison. The city was sacked along with about 30 other small Roman cities and towns by the Sasanian Persians in the middle of the third century, a time of turmoil and retrenchment for the Romans as their empire was beset by external enemies and internal rivalries.

The great archaeological value of Zeugma, Aylward explains, lies in the fact that the site was mostly intact, with military equipment, workshops, stunning mosaic pavements, and everyday objects left in place on the day when the Sasanian army swarmed and destroyed the city.

“It was mud brick wall collapsed on top of mud brick wall, tall stacks of debris that preserved the contents of the houses,” says Aylward. “From the archaeological record, we could determine how the sack played out.”

“Zeugma is a site of great archaeological importance because it is in a zone of the ancient world about which we knew very little until this rescue.”

William Aylward

Although the Zeugma rescue operation, also funded by the Packard Humanities Institute, could only excavate a fraction of the city before it was submerged, the evidence from the trenches revealed a city hastily abandoned before it was demolished and burned.

“They were warned. The city was emptied of its inhabitants. There were no skirmishes in the streets,” Aylward says, noting the absence of human remains in the sack layer.

But Zeugma was evacuated in haste, as evidence from the dig showed in dramatic detail. “Some of the daily operations of the town were frozen in time. In one building, mosaic tiles were carefully set out in pots, prepared for laying,” according to Aylward. In one dwelling, excavators found a jar, brimming with the carbonized remains of walnuts and pomegranates, left standing just where it was abandoned at the time of the Sasanian attack.

One intriguing discovery was the domicile of a junk dealer, dubbed by archaeologists the “House of Hoards.” Homes and shops were often combined, and the junk dealer’s raw material and tools of the trade — including a steel balance for weighing metal, old military hardware, jug handles, vessels, odd bits of iron and old coins — gave archaeologists a picture of a workshop that is the only one of its kind known from classical antiquity. One hoard of 462 bronze coins, minted all over the empire over a period of nearly 400 years, was dubbed by one scholar as “a junk box of foreign change” whose hoarder may have traded the coins to foreign travelers or simply held them as scrap.

Homes and workshops, explains Aylward, can reflect more about a society and how people actually lived than monumental structures like palaces and temples.

Zeugma’s violent demise and the foreshadowing of siege by its inhabitants is remarkably illustrated in the “Villa of Poseidon,” where the almost life-sized statue of the war god Mars was secreted in a closet along with an array of household goods, including a candelabra. “The owners never made it back to their home,” notes Aylward, “and the statue was found just as they had left it, laid away for safekeeping.”

For archaeologists, Zeugma promises to be a critical touchstone. The excavation, for example, revealed much about the everyday life of ordinary people on the margins of the Roman Empire in the third century A.D. Homes and workshops, explains Aylward, can reflect more about a society and how people actually lived than monumental structures like palaces and temples. The excavations at Zeugma provide one of the best records of the domiciles and domestic life of regular folks on the eastern edge of the Roman world.

Finally, because Zeugma’s sack has been dated with some precision (no coins struck after A.D. 253 have been found), the stunning floor mosaics most certainly predate that fateful year, providing a reference point that already has scholars pushing back by a century the dating of mosaics and wall paintings throughout what was once the Roman’s near eastern world.

Tags: archaeology, history, humanities