Annual poverty report shows economy improving, but support programs still needed

The good news is that jobs, earnings and wages are beginning to rise again in Wisconsin as the economy slowly climbs back from the recession, according to an annual in-depth study of poverty in Wisconsin conducted by researchers at the Institute for Research on Poverty (IRP) at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

The disappointing news, the recently released report covering 2012 finds, is that jobs in the state have not returned to pre-recession levels, and many of the new jobs are part-time and low-wage service sector jobs — so work-support programs, especially refundable tax credits and food assistance — are still needed to raise many working families with children above the poverty threshold.

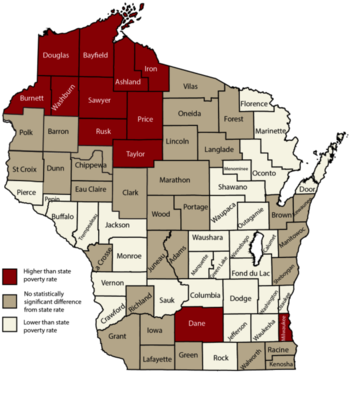

Counties in red have poverty rates above the state rate. Those in light tan are lower. Click to enlarge.

Source: Institute for Research on Poverty

“In times of need, a safety net that enhances low earnings for families with children, puts food on the table, and encourages self-reliance — as Wisconsin’s safety net does — makes a big difference,” says Timothy Smeeding, director of the institute and Arts and Sciences Distinguished Professor of Public Affairs at the UW’s La Follette School.

Study results are reported in the sixth annual “Wisconsin Poverty Report” by Smeeding and co-authors Julia Isaacs, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute, and Katherine Thornton, an IRP programmer analyst. The report’s findings are mixed but offer overall hopeful news as the state and nation continue to recover from the severe economic downturn that hurt almost all Americans, but especially the lowest earners and the most vulnerable.

While about half or fewer of the jobs lost during the recession have been recovered, the report finds that the upward trend in market income has led to a small reduction in the impact of social safety net programs on poverty, as higher earnings replace the need for public assistance.

In any case, pockets of poverty remain well above average for the state, especially in Milwaukee’s central city, but also in Madison and the Superior region.

Timothy Smeeding

The study, sponsored by the Wisconsin Community Action Program Association (WISCAP), uses the Wisconsin Poverty Measure (WPM), a state-specific poverty measure devised by the researchers that provides a more accurate picture of want in the state than is reflected in the official measure. The WPM also provides researchers and policymakers with an assessment of the influence of both the economy and public policies on poverty.

“Because we believe that the long-term solution to poverty is a secure job that pays well, not an indefinite income support program, these results give hope that as the economy slowly recovers from the recession, increases in earnings will continue to reduce market-income poverty, though we still have a long way to go to return jobs in Wisconsin to their January 2008 peak,” Smeeding says.

Smeeding and his colleagues found that the overall poverty rate in 2012, as calculated using WPM, declined to 10.2 percent, the lowest poverty rate since the measure was first utilized in 2009. The official poverty rate for Wisconsin for the same year was much higher, at 12.8 percent. The positive difference for child poverty is more dramatic: 11percent using the WPM and 17.9 percent using the official measure. Elderly poverty, on the other hand, was higher with the WPM at 7.4 percent than the official rate of 6.2 percent.

“In times of need, a safety net that enhances low earnings for families with children, puts food on the table, and encourages self-reliance … makes a big difference.”

Timothy Smeeding

The official measure was devised in the 1960s and has not essentially changed since then other than adjustments for inflation provides a clue. In addition to using a threshold based on 1960 consumption patterns, the official measure also ignores noncash public benefits such as Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, called FoodShare in Wisconsin) benefits and refundable tax credits — the nation’s largest and most effective antipoverty programs, Smeeding says. The official measure also ignores health care costs and work-related expenses such as childcare and fails to adjust for geographic differences in the cost of living.

The WPM addresses these shortcomings, Smeeding says. It determines poverty status by comparing a measure of economic need that includes childcare and out-of-pocket medical expenses to a measure of the economic resources available to meet that need that includes SNAP benefits and the refundable Earned Income Tax Credit. In the WPM, the resource-sharing unit is also modernized, to include all persons who share the same residence and are also assumed to share income and consumption (called family); in the official poverty measure, family is restricted to married couples and their children.

The end result, the report finds, is this improved measure is evidence of the effectiveness of safety net programs like food assistance and refundable tax credits.

—Deborah Johnson

Subscribe to Wisconsin Ideas

Want more stories of the Wisconsin Idea in action? Sign-up for our monthly e-newsletter highlighting how Badgers are taking their education and research beyond the boundaries of the classroom to improve lives.

Tags: poverty, research, The Wisconsin Idea