Missing WWII soldier may be found with help of UW-Madison scientists

Pfc. Lawrence S. Gordon snaps off a salute in an undated photo. The Canadian-born enlistee in the U.S. Army went missing in France on Aug. 13, 1944. UW–Madison DNA analysis may help confirm an unidentified body is actually Gordon.

Photos courtesy of Lawrence R. Gordon

On Aug. 13, 1944, German soldiers retreating from a U.S. Army reconnaissance patrol in Normandy blew up an armored car.

Pfc. Lawrence S. Gordon, a 28-year-old Canadian enlistee, had been riding in the Ford-build M8 Greyhound, and likely died in the explosion and fire.

Nearly 70 years later, Gordon remains among more than 73,000 members of the U.S. military listed as missing during World War II, but a Middleton, Wis., man and a UW–Madison laboratory hope to end that mystery and provide some closure for Gordon’s Canadian family.

“I’m sure my grandmother didn’t ever come to terms with it,” says Lawrence R. Gordon, Pfc. Gordon’s nephew and namesake, and a lawyer from Medicine Hat, Alberta. “My grandfather was raised in Sparta, Ill., but he never did go back to the U.S. after Lawrence died.”

Born in Saskatchewan in 1916, Lawrence S. Gordon was working in Wyoming when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. He and two of his brothers decided to take up arms. Lawrence and one of those brothers decided to enlist in the U.S. military, figuring it was better equipped than Canadian forces.

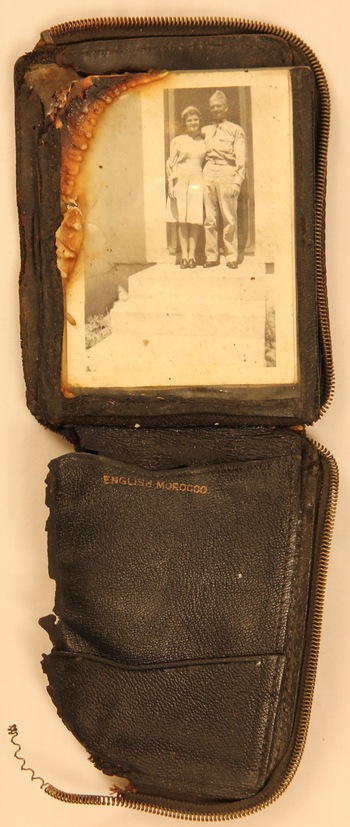

Charred and blood-stained — likely in an explosion and fire that took his life — Lawrence Gordon’s wallet is the only piece of his effects returned to his family.

Gordon ended up in the same reconnaissance company as Staff Sgt. David L.Henry, from Viroqua, Wis., a wounded survivor of the 32nd Armored Regiment’s Normandy campaign and the late grandfather of filmmaker Jed Henry of Middleton. Jed Henry became interested in the regiment’s history while making a film about his grandfather, and first heard the story of Pfc. Gordon from French historian Alexis Boban during a trip to Europe in 2011.

Henry dug into U.S. military files on Gordon, following the records to a body, designated “X-3,” buried in a cemetery for German soldiers in France.

Two days after the explosion of the armored car, X-3 was buried by U.S. soldiers as an unidentified American.

“Months later, that body is disinterred and, because it was wearing some German clothing, is re-designated as a German soldier,” Henry says.

But Henry, working in 2012, found evidence that X-3 could be Gordon. For starters, the body was found near the body of Pvt. James Bowman, who was riding next to Gordon.

“When they were hit, they were still wearing winter wool uniforms,” Henry says. “What we suspect is the guys who were in the country — for two months at that point — salvaged some German clothing that was a little bit cooler than the winter wool they were wearing.”

Bowman was identified from fingerprints, but the only thing that may have been collected from the scene connected to Gordon was a wallet — burned and bloodied, but still holding a few French bills and pictures of a uniformed Gordon with a girlfriend and his mother and nieces and nephews — that was returned to the Gordons in Canada with little or no explanation.

“I inferred there was a body somewhere, because the wallet is, I think, in pretty good shape,” Lawrence R. Gordon says.

“The French were treating it as a crime scene. We’re on one side of the tape, and on the other, they’re pulling bones out of the casket and bagging them like evidence.”

Joshua Hyman

James Gordon, brother to Pfc. Gordon, died in 1989 without visiting his sibling’s resting place.

“In our discussions before he died, I told him I would make a point of finding and visiting Uncle Lawrence’s grave,” Lawrence R. Gordon says. “He wanted the grave to be visited. But he was a farmer raised in Eastend in Saskatchewan, and he barely left.”

He did eventually visit a grave, but it was X-3’s resting place — a Nazi soldier’s grave.

“The French were treating it as a crime scene,” says Joshua Hyman, director of the UW-Madison Biotechnology Center’s DNA Sequencing Facility. “We’re on one side of the tape, and on the other, they’re pulling bones out of the casket and bagging them like evidence.”

Henry had convinced the German military graves commission and the French government to test DNA collected from X-3 to salivasamples from the Gordon family, with guidance from Hyman — who fell into the investigation by chance when Jed Henry walked into the Biotechnology Center on a blind hunt for help.

“The circumstantial evidence is good, but we knew it would come down to DNA,” Henry says. “We wanted to rely on the science to remove any doubt.”

Hyman and Charles Konsitzke, assistant director of the Biotechnology Center, were willing to provide the science.

“The circumstantial evidence is good, but we knew it would come down to DNA. We wanted to rely on the science to remove any doubt.”

Jed Henry

“These guys understood what we were trying to do,” Henry says. “Chuck understood the military bureaucracy and the hurdles we might encounter. Josh was able to help us understand the testing process.”

“This was an opportunity to help somebody and to work with older DNA, a skill we are developing here,” Hyman says. “Jed’s interest in Pfc. Gordon dovetailed nicely with our Molecular Archaeology Group, where we’re working with DNA and remains from people [that] are 4,000 to 8,000 years old to identify them and the social class they belonged to and which diseases they suffered from.”

Hyman expects to get a chance to run samples from Pfc. Gordon through DNA sequencers in Madison shortly after the New Year, after the French national crime lab takes the first crack.

But the trio who witnessed the disinterment of X-3 do not need much more convincing. The sample collection included a look at the body’s lower jaw, which bore remarkable resemblance to Lawrence S. Gordon.

“The spacing, the tooth missing from the exact spot Uncle Lawrence had one removed, it’s either him or one hell of a coincidence,” Lawrence R. Gordon says.

The Canadian-American team was greeted with much appreciation by the European governments, who were willing to undertake the testing even though the U.S. military never thought Henry had provided enough evidence to justify it.

“The spacing, the tooth missing from the exact spot Uncle Lawrence had one removed, it’s either him or one hell of a coincidence.”

Lawrence R. Gordon

“We thanked the representatives from the German war graves commission when we were there, and they thanked us right back,” Henry says. “They have even more soldiers missing, and our search helped open cooperation between the French and the Germans.”

Lawrence R. Gordon hopes U.S. acceptance of citizen investigators follows.

“What Jed has done for us means everything,” he says. “We hope that for the American military it means that people outside their system can contribute.”

He also wonders if Hyman’s analysis can uncover some lighter scientific knowledge. His uncle Lawrence’s girlfriend, the one in the wallet photo, says the young soldier was a good dancer.

“If that’s true, he’s the only one in the Gordon family, ever,” Lawrence R. Gordon says. “That alone might be worth some testing. We should see if Josh can identify which gene that is that the rest of us don’t have.”

Tags: biotechnology, DNA, history, veterans